My Favorite F***ing Movie is a personal exploration of sex through film, released monthly.

When I was thirteen, my concept of coolness revolved largely around the things my older brother deemed cool.

I assumed my brother’s tastes were a cheat sheet to the preferences of all cooler, older people, and a window into the secret language and desires of older boys, in particular. The four years between my brother and me felt like a chasm by then; just wide enough to ensure that we were never in the same school, never shared classes or even a cafeteria. I had abstract crushes on all of his friends, but I was too shy to even speak to most of them.

Instead, I noted and catalogued their favorite pieces of pop culture, as if by collecting and eventually consuming them myself, I might be transformed into someone else. Someone knowing, and therefore worth knowing. (This was the childhood fantasy of most online millennials, I’ve since gathered.) I yearned—goddamn, did I yearn, so much that my wrists got sore… but for what, exactly, I couldn’t quite pin down.

My fixation was less about broaching any actual act of sex with someone else—I wouldn’t even have my first kiss for another two years—and more about being the kind of person who could hang. I felt a nagging desire not to be a boy, and not to be a girl amongst boys, but simply to be one of the boys.

I was deeply inexperienced, and also deeply curious in a way that implicitly felt wrong… for a girl. None of my friends seemed to hold the same appetite I had, this hunger for something intangible, something that made them ache. Or rather, if they did, they weren’t sharing it with me. Like anything that might mark me as different growing up in the early aughts, I assumed that meant it was bad and I should hide it.

I knew by then that it was okay for boys to want sex, to be interested in it, to talk about it. It was natural, almost a requirement. But for girls? It was more complicated.

(Though Allison Reynolds summed it up rather succinctly in The Breakfast Club: “If you haven’t, you’re a prude. If you have, you’re a slut. It’s a trap. You want to, but you can’t, and when you do you wish you didn’t, right?” I realized quickly that what she was saying applied across the board to girls committing any act of sexual pleasure, even masturbation.)

I couldn’t help it, though… I wanted to know what the boys knew.

My friend and I snuck down to the basement one night, where my brother’s borrowed copy of Go was still sitting inside the DVD player. My mom was fairly permissive, but her whims could be unpredictable. Better to seek forgiveness later, I reasoned, than to ask permission and risk a straightforward no.

And then the film unfolded in all its vulgar, wanton glory. My friend cringed away from the screen in embarrassment, just as I leaned in.

Go is an unquestionably horny film, the entire narrative saturated with innuendo, and if not with literal sex (there’s only one sex scene, all told), then the ever-present promise of sex, shimmering and imminent somewhere on the horizon. As if, for a certain type of person, it always was.

I’ll condense the plot as much as possible, as it’s a winding three-parter, and quite frankly you should have watched it by now. (It’s been 25 years, what are you waiting for?)

The film intertwines the stories of three sets of characters living in Los Angeles: Ronna (Sarah Polley), who works at a supermarket with friends Claire (Katie Holmes) and Mannie (Nathan Bexton), and who needs to make rent fast in order to avoid getting evicted on Christmas Day. The second segment follows Ronna’s co-worker, Simon, on a road trip to Las Vegas after he convinces Ronna to cover his shift. The final thread involves Adam and Zack, soap opera actors and lovers who are working with the police to entrap their drug dealer—who happens to be Simon. Because Ronna is covering Simon’s shift, Adam and Zack approach her for the drugs instead, and since she’s desperate for the money… you see where this is going, right? The three stories interlace and overlap, Pulp Fiction-style.

I was attracted to at least half the cast in one way or another: Sarah Polley, with her bedroom eyes and that penetrating glare. As Ronna, she had an aloof, almost masculine nonchalance about her, a disinclination to smile or feign politeness that I found alluring in a way I didn’t yet understand. I wanted to be her best friend. I wanted her to drag me into her adventures, which were undoubtedly more grown-up and exciting than any I’d stumble upon myself. (The idea of needing to make rent sounded romantic in the way that it only can for a kid who’s never had to do it.) I also wanted to see her boobs, which appeared, to my layman’s eye, to be perfect.

Katie Holmes had been an infatuation since Disturbing Behavior. She was one of the most effortlessly beautiful women I’d ever seen, and over the next few years, I took great pains to emulate the mixture of her briefly-lived alternative leanings—dark eyeliner, artfully messy hair, and numerous chokers, natch—and her sheen of girl-next-door innocence. To me, it seemed a brilliant costume, though the latter part was more of a coping mechanism than a conscious choice.

There was Nathan Bexton, who looked comically similar to one of my brother’s friends and was thus an instant, if tepid, crush. He had the same floppy, harmless demeanor as any nice suburban boy I’d come across, and those were basically the only boys I knew. But I didn’t think about them when I was alone in my room at night. I didn’t think of anyone.

But then, like a revelation, came Todd.

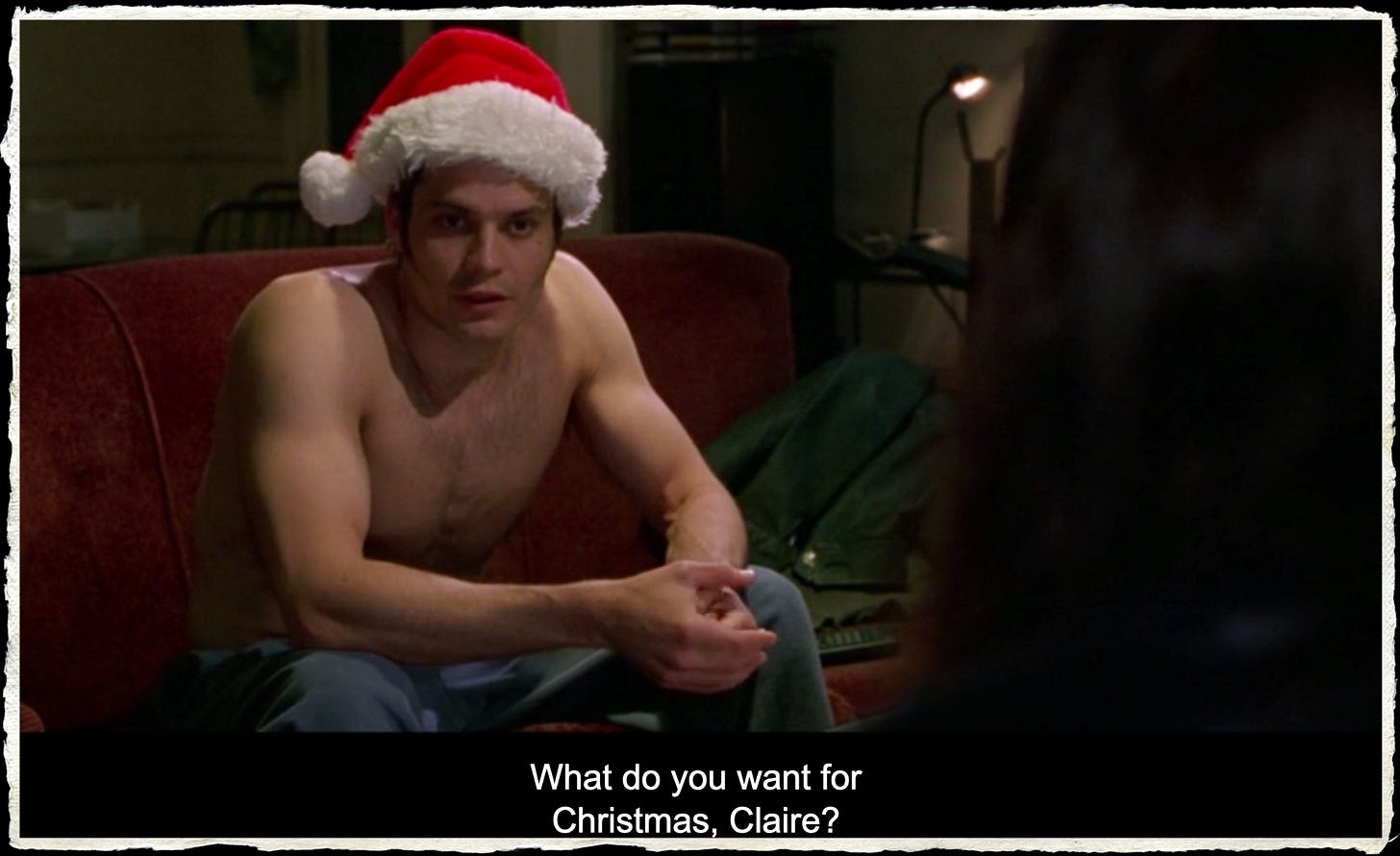

God-tier Timothy Olyphant, lounging around his dank apartment in nothing but a pair of slouchy sweatpants and a Santa hat. Wild hair and eyes like bruises. I saw him, and instantly I knew. This was what it was all about.

His slim-muscled frame and unhinged stare would become a blueprint for my attraction towards disheveled, dirtbag men for the rest of my life.

Olyphant plays Todd, drug supplier to Simon. (I hope you’re keeping up, because it’s only going to get hairier.) Unable to pay upfront for the ecstasy she needs to sell to Adam and Zack, Ronna offers to leave something at Todd’s place as collateral. Todd asks for… Claire, who very (very!) reluctantly agrees to stay.

Claire in the movie may have been horrified, but me? This Claire? Thrilled. These were exactly the kinds of shenanigans I’d known Ronna would get us into.

As Ronna attempts to wrap up her deal with Adam and Zack—and fails, barely making it out of the situation without getting arrested, and only after flushing the drugs down the toilet—Claire is stuck sitting across from Todd on his grimy couch while he glowers and makes vaguely threatening sexual commentary:

Todd: What do you want for Christmas, Claire?

Claire: I don't know.˙

Todd: Do you want to get laid?

Claire: No.

Todd: No, you don't wanna get laid, or no, you do, but you don't wanna get laid – with me?

At the tender age of thirteen, I could not imagine a more erotic situation. Oh, to be forced into close proximity with a boy I was afraid to speak to! If only the universe would conspire with me so. Moments later, unprompted, he delivers the “Are you a virgin?” scene from The Breakfast Club:

“Come on, Claire. Answer the question. Answer the question, Claire!”

It was like he was speaking directly to me.

I was a sheltered kid—sex wasn’t taboo in my house so much as casually unstated—but I was also a preteen on the burgeoning World Wide Web, possessed of a healthy curiosity. My knowledge base was there, but it was scattershot. It was also skewed due to easy access to porn (easier, I should say; you haven’t lived until you’ve covertly browsed XNXX on the family computer while listening for your mom’s key in the front door). I knew what all the sex acts were in great, often frightening anatomical detail, but I had yet to grasp what made most of them sexy. My concept of “sexy,” in general, was almost entirely undeveloped.

Todd changed things.

The film shifts to Simon’s perspective during the second story, the Las Vegas trip, which is by far the most overtly sexual segment. It opens in the car with Simon and his three friends—Marcus, Tiny, and Singh—recounting highly-embellished sexcapades to one another. Turns out Tiny’s story about knocking a contact out of a woman’s eye with his dick—a sordid tale of which he is very proud—was stolen from Marcus, who has the concrete details to prove it.

Over lunch, Marcus explains to the other three how they can have hour-long orgasms by practicing Tantra; all it takes is a little discipline. Tiny remains unconvinced: “Call me old school, but I’m for coming-and-going,” he says while rhythmically high-fiving his best bro in what can only be a salute to premature ejaculation.

Everything about the Las Vegas trip is crass and larger-than-life, a silicone-pumped-up fever dream of male-gazey, testosterone-fueled sex and posturing.

Marcus clearly fancies himself the sexual guru and leader of the group, and Simon gloms onto him like a nasty habit—but not before crashing a wedding and sleeping with two of the bridesmaids. It’s the aforementioned one and only sex scene, cut short when Simon’s gyrations accidentally start a fire.

The two men adjourn to a strip club, where Simon requests lap dances from a pair of dramatically surgically-enhanced strippers. It should come as no surprise that Simon can’t keep his hands to himself; he gropes one of the dancers, a breach of the club’s rule and common decency, and only escapes by shooting the bouncer in the arm and taking off.

The narrative eventually circles back to Claire and Todd, who run into each other early the next morning at the same restaurant. She imposes herself on him, “thanks for buying me breakfast,” but then offers to leave if he’d rather be alone. He seems to take a beat to consider, then says it’s fine.

“See, I knew you weren’t all evil,” Claire quips, and the look that crosses Todd’s previously stony countenance—surprise, tinged with a slightly bashful tenderness–would go on to launch approximately ten thousand fantasies over the course of my teenage years. “I can fix him” was my mantra straight through high school, baby.

In contrast to the Vegas story, which only reiterated the rather unsettling perspective on sex I’d encountered in online porn, Claire and Todd’s flirtation was tamer and more approachable, while still retaining a hint of danger. There was an electrifying volatility to Todd, tempered by that sardonic smile and a body that I was sure housed a heart of gold, among other assets.

The two end up talking—about Todd’s hatred of The Family Circus, for one thing; I sense a grumpy/sunshine romance novel in the making—and Claire gives a miniature soliloquy about her affinity for Christmas surprises. At this point it becomes clear that the surprise is her attraction to Todd, whom she deems “only medium cute” (I can hear my inner teen scoffing), and the two end up making out in a stairwell.

The moment was… transformative.

I’d never seen anything so sexy as Todd’s chiseled forearms, his nails dotted with remnants of black polish, large hands reaching to cup Claire’s gorgeous face and skim beneath her shirt as they kissed like they needed each other for air; or Claire reaching down to unbuckle the belt securing Todd’s low-slung jeans on his hips.

It wasn’t just that they were physically attractive in ways that seemed specifically designed for me. It was the sexual tension simmering between them from the beginning, and the subtle change in the air from scary to scary-sexy. It was that fucking look Todd gave Claire in the diner. It was, “What do you want for Christmas, Claire?”

Their encounter is cut short by the Vegas bouncer chasing down Simon, the fantasy shattered when Claire sees Todd interacting with other gormless criminals in the cold light of day.

Go is a bit of a tease that way: it’s all setup and no follow-through. Everyone talks about getting off, but almost no one actually does it. That’s not a criticism, though; it was the most relatable part for me back then.

Much has been written over the years about how Go captured the zeitgeist of the late 90s. Now a quarter-century since its creation, it’s a nostalgic remnant, a melancholy-tinged, pre-Y2K artifact embodying a simpler time. Watching it today makes me nostalgic for an era and a culture I wasn’t even old enough to experience myself.

But Go was like the older sister I didn’t have, ushering me into teendom with illicit tales and promises of what life could be, someday. Wild and scary, heady with lust, and full of odd and fascinating people I had yet to meet. Someday, when I was old enough, and cooler.

Go gave me something specific to thirst for. And not only in terms of sex, but, just as vitally, in film. I hadn’t yet unearthed the filmmakers who would really push my buttons; I still had the discovery of Gregg Araki to look forward to, and it would be a few years until I finally made a friend who shared my proclivity for cinema with sex and sensuality. But Go provided me a context, a foundation for new languages I was only beginning to discover, let alone learn. It helped shape my desires and gave me a new trajectory.

There was so much to experience and explore and enjoy in the world, and suddenly I could hear the universe whispering all around me,

Go.